Sex/Ethics/Practice: Looking at an Old Tale

By Rafe Martin©

In yesterday’s talk we saw the Bodhisattva as perfect, and perfectly perfecting the paramita of dana or selfless generosity by giving his body to a starving tigress as food. Today we’ll see him closer to home, more like us, working hard at perfecting a paramita but clearly, he still has a ways to go. Yesterday the jataka was about taking a selfless leap. Today it’s about a fall. For the Buddha, in his own long practice toward Buddhahood, (as dramatized by the jataka tales), made mistakes. Just like us. No difference. How he dealt with them is what’s important. And revealing. So let’s see how he worked with his own failures and shortcomings. To do that we’ll take up the story of “Gentle Heart,” the Mudulakkhana Jataka, # 66 in the Pali Jataka and examine it in light of sila paramita — perfection of morality.

Long ago, when Brahmadatta reigned in Benares, the Bodhisattva was born into a Brahman family in the Kasi country. (There are jatakas where he is born into poverty but here he’s pretty high class, though not necessarily noble.) His youth and childhood were happy and yet, when he was grown and had finished his education, he saw little profit in the ways of the world and chose instead the hermit’s path. Retiring to the Himalayas he built a hut and devoted himself to meditation. Making a strong effort, he attained to the selfless knowledge of prajna, and entered the Awakened life. There he lived, high up on the peaks, absorbed in bliss.

One day he ran out of salt, vinegar, and other staple items. Piling his tangled hair up in a knot on his head, he straightened his bark clothes, put an antelope skin over his shoulder, and thus properly attired headed down the mountain to Benares to gather alms.

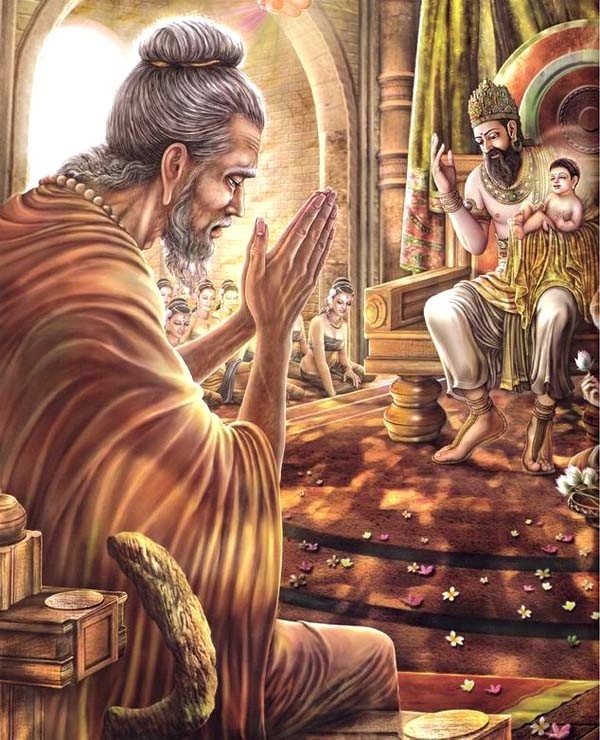

As he walked along the streets receiving his alms in the traditional way of a religious beggar, he came to the palace of the king. The king, glancing from his window, saw the youthful ascetic standing there bowl in hand, and was struck by the man’s dignified, serene bearing. He invited the ascetic into the palace, him offered a golden couch to sit upon and delicacies to eat then asked for teaching. The ascetic gave them freely and well, exhorting the king to be charitable, to think of the welfare of others, to regard all beings as his own subjects, to examine carefully all legal cases put before him, to examine fully and circumspectly all calls to war and killing, and, while still immersed in the many and varied responsibilities of kingship, to never cease seeking wisdom. The king was impressed and wanted his whole family and the palace nobles to also benefit from such inspiring words. So he requested that the hermit remain. “I’ll have a hut built in my gardens where you can continue your meditation uninterrupted,” he said. “All I ask is that you teach me, my family and the court. I hope you will accept this sincere request.”

The hermit did accept, and was happy to guide the king and nobles along a path of generosity, compassion, and wisdom. The king benefited and so did the people. And there the ascetic lived for sixteen years, maintaining his own practice and coming regularly to the palace to receive meals and offer teaching.

At one time the king had to go off to settle a border dispute. He told his queen, Gentle Heart, that while he was gone, she should make sure that their teacher continued to receive his meals, and, he added, “Request him to continue teaching as well.” Then the king left.

While the hermit’s meal was being prepared in the kitchen below, the queen took her bath. After the bath she put on her robe and, as the hermit was late in arriving, she lay down on her couch and closed her eyes to rest, trusting she’d be notified when he arrived.

The ascetic rose from his meditation and, seeing that the hour was late, instead of walking to the palace as he usually did, this time he rose up into the air and flew swiftly there, entering the palace unannounced through a window on the second floor.

The queen lay half asleep on her couch. Hearing the rustling of the ascetic’s bark clothing, she rose. As she did, her robe fell open and the hermit saw the queen’s naked beauty fully exposed. He gazed and could not turn his mind or eyes away. A shiver ran through him. For all his insight, wisdom, and charity he was not prepared. And he fell, like a tree cut by the ax. Realization left him, and from that moment on, all he knew was desire, flaming and overwhelming.

He stood there with his bowl in his hand and could not say a word. Stammering words of pardon and mumbling that he’d suddenly been taken ill, he walked down the stairs, his power of flight gone, and stumbled back to the garden and his hut. There he lay on his bed and for seven days, without eating or drinking, there he remained, floored, overcome by lust. All he wanted was Gentle Heart; wanted her naked as he had seen her. It was all he could think of. Nothing else mattered.

The king returned from the borders and asked after their teacher. Hearing that he was ill, he hurried to the hut in the garden. And there he found the hermit looking very poorly, indeed. When the king asked what he was suffering from, the ascetic answered honestly, “It is lust, Sire.”

“Lust? Lust for whom?” asked the king.

“Gentle Heart,” answered the ascetic. “I chanced to see her naked and, before that image, my mind falters. I cannot get past it.”

The king was silent. He looked at the sage, his teacher, and saw him emaciated, with dark circles under his eyes, bereft of radiance. At last he said, “If that’s how it is, then you shall have her. You’re a good man and have been an excellent teacher. Perhaps it’s meant to be. Though unexpected, perhaps that’s the karma. So get up, eat this food I’ve brought for you, bathe, and prepare for your new life. I’ll be at the palace. Come when you’re ready.”

The king went home and said to Gentle Heart. “Our teacher is in trouble and needs our help. He’s wise, but not worldly. The sight of you naked inflamed his lust. I think he never really had to deal with it before. He’s like a teenager, and doesn’t know how to handle it. I told him he can have you, and that you will go with him. Wait. Let me finish. I told him that because I trust you and your wisdom. Can you think of anything we can do to help him? He’s having a terrible time.”

Gentle Heart was silent. Then, “All right,” she said. “Here’s what we can do.” And she told him her plan.

When the hermit came to the palace the king welcomed him, then ceremoniously presented Gentle Heart to him. “Now you are his,” said the king, “and no longer my queen. Go with him in peace.”

So the hermit, his heart pounding, left the palace with the beautiful queen by his side. But they had hardly taken a dozen steps beyond the gates, when Gentle Heart turned to him and said, “Where shall we live?”

“Why, in my hut in the garden. That’s where we’re going now.”

“No,” said Gentle Heart firmly, “that will not do. It’s hardly big enough even for you. It’s not fitting that I, a queen, should live in such a place. Go back to the king and ask him to give us a bigger dwelling.”

So back the ascetic went. The king stroked his beard and seemed to contemplate the problem. “Ah,” he said, “there is a broken down sort of place, an old cottage on the palace grounds. It’s been left in pretty bad shape, but if you fix it up, it’s yours. It should suit your needs.”

So the hermit and Gentle Heart went to the broken-down cottage. “The size is all right,” she said looking at the building and grounds. “But it needs a lot of work.” When they stepped inside she frowned and shook her head. “It’s disgusting! I could never live here the way it is. Look at this filth! Animals have denned and birds nested here. Vagrants have camped here, too. Look at that pile of junk! And what an awful smell! No. I won’t step back inside this place until it is fixed-up properly, scoured, cleaned, and repaired, re-plastered, and painted. Remember, I was a queen, and I am beautiful.”

“I know it,” said the ascetic. “And I can’t forget it. Go and stay in my hut for now. I’ll remain here and get this all fixed up. When it’s ready I’ll come for you.”

“You’ll need tools,” she called as she walked off. “Go back to the king and ask for buckets and shovels. You’ll need hammers, saws, levels, paints and brushes, and plasterers’ trowels. We’ll need furniture. You’ll have to make couches and a bed and a stool. We’ll need cups and plates. We’ll need a good stove. Oh, and a pen for the animals. We’ll need a cow at least for sure. And don’t forget the garden. Remember, we’re on our own and it’s up to you.”

“Never fear,” said the hermit. “You are mine, and I will do everything necessary to make you happy.”

Gentle Heart went to the hut in the garden. The ascetic went back to the palace. Back and forth he went many times carrying hammers, saws, axes, trowels, shovels, nails, brooms, buckets, cups, paint, seeds. When all had been gathered he set to work.

He swept out the rooms and burned the trash and filth. He hammered loose boards back into place. He fixed the thatch, re-plastered walls, carried buckets of stone to strengthen the foundations. He painted the rooms. He dug a garden, planted seeds, built a pen for cows and goats. He labored for days. Finally, exhausted, but in great excitement, he hurried to retrieve Gentle Heart and bring her to the home he had prepared, where she would at last be totally, entirely, rapturously his.

Gentle Heart came back with the ascetic. “It needs a door,” she said.

“Oh,” he said. “Now?”

“Definitely, now,” she said. “How could we move in without a door? I possess things someone might want to rob.”

“You’re right. I didn’t think of that,” he said. “I’m not used to owning things, or having to protect them.”

“You’ll learn,” said Gentle Heart. “Plus, we’ll need our privacy, won’t we?” she added softly. “Come for me when it’s done. I’ll be waiting,” she added with a warm smile.

Heart beating, the hermit once again set to work. He sawed and planed and hammered. He forged iron hinges. He measured, cut, and re-cut. Finally, he lifted the door and hung it in place. It looked good. It would wall out the world. Then he hurried to retrieve the beautiful Gentle Heart, his Gentle Heart.

Shyly he led her to their home. She smiled as she looked over the exterior. Good walls, roof, animal pen, door. She stepped inside. “It’s lovely,” she said looking around. “Truly perfect. You’ve done a great job. Now, come with me.” Closing the door, she took the ascetic by the hand, and led him to the bed. They sat down facing each other. She put her hands on his broad shoulders and could feel his heart pounding, pounding wildly. She reached up, took hold of his beard, drew his face close to hers, looked him in the eyes, and said, with surprising force, “You are a good man. And you are a holy man, a sage. Have you forgotten yourself?”

And just like that, in a flash, he saw it all—how he’d lost his Awareness and gotten lost in a little heavenly dream, saw how his mind had been overcome, his practice long since flown away. He was startled and ashamed, shocked, really, to see how desire had so quickly inflamed, and then dominated, his mind. And he saw, too, how unprepared and raw he still was, how unready yet to give guidance to others, how immature still in his actual embodiment of the Way. And then he remembered his own deep Vows. And with that, he regained his underlying determination to awaken fully and be of help to all beings who face loss and illness, aging and death without a guide, a bridge, a raft. He saw, too, that he stood poised on the edge of a knife and that, so far at least, no real harm had been done. “Gentle Heart is not mine,” he thought. “She is the king’s wife, the queen, and has been both wise and very kind. And so has the king. To go further now would begin the betrayal. That is where immorality would start.”

The hermit stood up. “I’m not ready for you,” he said to Gentle Heart. “Tell the king, too, that I appreciate his sacrifice, and all he’s done for me. He’s a wise, brave, and unselfish man. I’m embarrassed by my failure. I thought I was beyond all that. You’ve opened my eyes, and dealt skillfully with me, too. I thank you.”

With that he bowed to the beautiful Queen, then walked out of the now lovely cottage. With Awareness regained and powers restored, he rose up into the air, and flew back to the Himalayas. “Lapses like that won’t do!” he admonished himself as he flew through the sky. “Flying has its uses, but walking on the ground is not as easy as it looks from up here. It might be wiser in the future to master fewer special powers, and more ordinary ones. I was hasty. Those people know things I don’t. Back to work.”

The snow-capped peaks were approaching. Soon he’d land, find his old hermitage, restore it, and settle down again to mastering the endless way.

Gentle Heart Jataka Sila Parmita, Perfection of Morality

This is an especially important jataka in our time. Sila or, morality, is an important but, sadly, often not well-enough upheld paramita. Too many spiritual teachers have fallen here, not having seen the connection between morality, or sila paramita, and practice/realization, or prajna paramita clearly enough — with disastrous consequences for their whole community, for us to take it lightly or think that it’s just an old tale. Roshi Kapleau, used to say, “Zen is not above morality, nor morality below Zen.” From the perspective of the paramitas and of the jataka tradition, the spiritual and ethical cannot be teased apart without doing violence to both.

In most jatakas, the Bodhisattva appears as a paragon of practice virtue. But if we think about it we must see that behind all such moments of self-mastery must surely lurk earlier, equally earnest but, for one reason or another, unsuccessful attempts whereby the Bodhisattva just works and works at it. This important tale shows the Buddha in process, hard at work. And it shows that because the Buddha was just like us, he, too, made mistakes and had to learn from them how to grow and change.

Indeed, sprinkled through the jatakas are accounts, some in human, some in animal or other realms, in which the Bodhisattva screws up, goofs, or fails. In one he’s a foolish jackal who finds a dead elephant. “Lots of lovely meat there,” he thinks as he greedily gnaws his way in. He then lives inside the elephant happily chewing away, safe from hunger, storms, cold, and predators. But the carcass dries and shrinks even as he gets fat, and, when he decides to leave, he can’t get out. He becomes terrified and desperate. Making a great effort he shoves with all his strength and forces his way it out through the dead beast’s anus. Minus his fur. Naked and exposed for the first time he clearly sees where greed leads, and resolves to never be so foolish again. It’s funny, but instructive. And some actual observation of jackals in the wild might lie behind the tale. And it’s amazing and humbling that Buddhist tradition itself authorizes us, in the jatakas, to see our founding teacher in this somewhat flickering, dubious light. By so doing it enobles us with truth and reality rather than infantilizing us with projection and wish-fulfillment.

This jataka of the ascetic and the queen looks right this difficult and often painful process of how, if we’re serious about our practice, even mistakes can be important in our growing and maturing. In the introduction to the story in the Pali Jataka, the “tale of the present,” tells how the telling of this past life story came about.

Tradition says that a young gentleman of Savatthi on hearing the Dharma preached by the Buddha, gave his heart to the Doctrine. . . . and renounced the world for the life of a monastic. One day he saw a beautiful woman and struck by her appearance, for pleasure’s sake gazed upon her. Passion stirred in him and from that day, under the sway of passion, he lost his enthusiasm for the practice.

When his friends in the Sangha became aware of his state they took him to the Buddha who asked, “What is troubling you?” “Sir, I was on my round for alms when, violating the higher morality, I raised my eyes and gazed for a good while on an attractive woman. Then passion was stirred within me. That’s why I’m troubled.” Then said the Master, “It is little marvel, Brother, that when . . . you gazed long for pleasure’s sake you felt the tug of desire. Why, in bygone times, even those who had won the five Higher Knowledges and the eight Attainments, those who by the might of Insight had quelled their passions, whose hearts were purified and whose feet could walk in the skies, even Bodhisattvas, through gazing too long in violation of the higher morality . . . lost their insight … If passion could stir in even enlightened and pure-minded Bodhisattvas, shall passion not also pose a challenge for you?” So saying, he told this story of the past. (Adapted from Cowell, Ed. Jataka Stories. Translated from the Pali. Vol 1, pgs. 161-2.)

That is, he told this story, set ages ago, when he himself was already an enlightened sage, so pure he could fly through the air, and yet his practice is not really complete. This jataka reveals that even such a high degree of Insight is no guarantee against self-centered, unskillful actions. So the lesson is, “Stay alert!” But if you don’t, then you’d better be willing to work at it!

This determination to uphold sila, and adhere to a code of morality—one of the oldest in Buddhism being the panca sila—or five general precepts—not killing or harming others, not taking what is not given, not lying, not selfishly mis-using sexuality, or indulging in liquors or drugs that confuse the mind and so cause careless actions—is highlighted by this story, and shown to be spiritually crucial.

We all make mistakes, but to do the least harm—the oldest morality– is always wise. Not imposing the demands of our own self-centeredness onto others gives them the space to be themselves. So sila, or morality, is dana, or generosity, too, as it is all other paramitas as well. And all others are sila, and likewise, dana. Morality, is generosity, generosity, morality. And so on. Each paramita is whole and complete, and simultaneously each is first, center, and last in the series.

Our story begins twenty-five hundred years ago, when, in order to help a monk, the Buddha generously reveals that he, himself, wasn’t always perfect, that he didn’t descend from on high, ready-made. Instead, he lets the monk, the sangha, and us right now, peer behind the scenes, to see the dedicated work it took for him to get to where he is. He shows us that twists and turns, stumbles and difficulties, challenges, trials, missteps and failures, are part of the Path. Are, in fact, human.

In this jataka, feeling desire wasn’t the problem. Being overcome by it was. Getting caught by desire, the bodhisattva has to be helped to face his error and deal with it by more worldly friends. But what friends they are! The king and queen are solid, can stand on their own feet and, without either judging or getting drawn into their teacher’s fantasy, are able to act skillfully and wisely. They also seem to have a well-developed sense of humor and, by using it, present us with a terrific model for lay practice, and its potential for integrity and maturity. They seem to be pretty far along on the Path themselves, really “together,” independent, and functional, individually and as a couple. They have wisdom, compassion, courage and skill—enough to bring their own teacher to the point where he himself can grasp what’s going on. They might not be as enlightened as he, but they’re certainly no slouches. They are not judgmental in the least. But neither are they willing to allow unskillful, self-centered behavior on their teacher’s part to flourish. They will not enable it. That’s a razor’s edge. To walk it takes, along with their insight and courage, decisiveness and skill. It might be their innate character being revealed. But it might also suggest that for sixteen years they had good teaching.

And actually, not surprisingly, the Buddha-to-Be offers us a strong model, too, but it’s a model of process. He’s above the royal couple in prajna, (non-dual wisdom), but not as well grounded in jnana, (knowledge), or upaya, (skillful means). With their help he wakes up to his error, takes responsibility, apologizes, and gets back to work on himself at another, deeper, more focused and determined level. He uses his own mistake to mature further. Recovering sila, he embodies dana. He shows us the Way.

And that’s the Path. It’s not about being perfect, but of committing oneself perfectly to the sincere practice of perfection, as Aitken Roshi calls it, a steady commitment to doing one’s best. Zen Master Dogen writes that it’s not the great, vast, empty ocean that’s most important but, “the harbor and the weir,” that is, the complex, complicated, personal places, even stuck places, where the vast empty ocean meets the turns, twists, and sandbars, where we, ourselves alone, just as we are, incomplete and half-blind/half-awake, are personally responsible for the practice—for zazen on the mat, and the actualization of the precepts and paramitas in our lives.

The jataka also clarifies another important point. Let’s not expect enlightenment to magically solve all our problems. Roshi Kapleau used to tirelessly repeat, “It’s not the enlightenment that makes the person, but the person who makes the enlightenment.” It’s up to us to make real in our lives what practice/enlightenment reveals. The sage is so enlightened he can fly, but his practice is clearly not yet fully integrated into his life. So there’s work to be done.

Now, periods of retreat are always going to be helpful. And for some people, as for the Buddha in a number of his past lives, being a full-time monastic might be the way to go. But most of us these days find, also like the Buddha in so many past lives, that we need to be out in the so-called “world,” where our vows, aspirations, and practice will get tested and refined, places where we also run the risk of failing, if we’re really going to mature. And this, too, as this jataka shows, is the tradition.

The hermit was isolated on his lofty mountain peak of pure practice where he could perfect his flying just fine. But without other people around, what chance did he have of perfecting sila? To do that, to fulfill his own bodhisattva vows, he had to come back down.

(Supposedly the Buddha once admitted that if there had been another desire as challenging and as potentially consuming as sex, he might not have been able to get through it and make the grade. One such challenge was enough. Clearly, as this jataka shows, he knew what he was talking about.)

Many years back, in the early seventies, Roshi Kapleau was giving a workshop in Ann Arbor at the University of Michigan. They sat zazen, he gave his regular workshop talk, and then it was time for questions. Someone raised a hand and asked, “When was the last time you had a sexual fantasy?” Roshi’s attendant at that event said that when he heard that he was floored. He. Not Roshi. He expected Roshi, who did not suffer fools gladly, to either brush it off, or put the questioner down, or maybe refer to something long ago. Instead Roshi said, “We were coming up in the elevator to the room where we’d be holding the workshop earlier today and there was a very attractive woman in the elevator with us. That was the last time.” The room erupted in laughter. This was not a guy sitting up on a mountaintop looking down at them. Sila, morality, is a paramita, a practice to be perfected. Without the structure that moral codes provide, things can go easily haywire. But sila does not mean repression. Roshi was fully aware, and not ashamed of the workings of his human nature. Yet, at the same time, he led a very pure, celibate life, a life of pure practice, while at the same time remaining ordinary through and through. As the well-known Zen story of the two monks at the river goes, the one who carried her across, set her down on the other side, the one who didn’t carry her kept carrying her in his mind. So, too, it seems the guy who asked the question sadly didn’t get it, and was disappointed in Roshi’s answer, in his admitting that he had had a passing sexual response to an attractive woman. The old beat goes on. We all live with it, work with it.

One of the most open pieces of writing by a senior Zen teacher about this issue was something of Aitken Roshi’s that appeared in Turning Wheel, the publication of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, in the ‘90s. In his piece, written when he was in his late 70’s, Aitken Roshi publicly questioned himself as to whether or not he hugged the younger and, as he quaintly put it, more “nubile” women in his sangha, in exactly the same way he hugged the older ones. There he was working on sila paramita right out in the open, examining himself by its light with great integrity.

And just to be clear, this jataka is not saying that sex is bad. That would be like saying the core of life itself is somehow bad. The Buddha, too, after all, had many many lives as a husband and father. Even in the final jataka before his birth as Siddhartha Gautama, when he is the Prince Vessantara, he was married with children. Indeed, even as Siddhartha he is married with a child and, if the accounts are accurate, a palace of dancing girls – that is, a harem! So desire and sexuality were part of his life for a long long time, countless lives according to the jatakas, almost right up until full Buddhahood had been attained. The problem here, in this story of the ascetic, is simply that as an ascetic, the Buddha-to-Be had taken vows of celibacy. And he was a teacher. So to fall into lust — a drug of the mind—not love, with his own student’s wife who was also a student, would be both inappropriate and very unskillful. If his real aim was to alleviate suffering and save the many beings, he’d veered off target in choosing to please himself and satisfy his own desires at others’ expense.

And does it have to be about sex at all? Couldn’t we be talking about anything that floods our minds with desire and makes our palms sweaty and knees weak—the new job, the new contract, the new house, the new car, that doggie in the window, those cool shoes, the 52 inch HD LED flatscreen TV, the computer with all the bells and whistles, the latest iPhone, the original oil painting that would be perfect for the living room wall, the Japanese teapot, the new Buddha . . . whatever? There is a jataka, “The Spade Sage,” Kuddala Jataka, # 70 in the Pali collection of 550, in which the Buddha in a past life is a gardener who is so attached to his gardener’s spade that he has to struggle mightily to rid himself of this overwhelming attachment—and it’s just a shovel! He fails six times, but on the seventh, making a truly determined and strenuous effort, he really lets it go. And when he does, he is overwhelmed with such joy, such a sense of triumph that it is like what a king might feel in conquering an entire army in battle, and winning a new kingdom. There’s another jataka, the Guttila Jataka, No. 243 in the Pali Jataka, in which the Buddha is a master musician who is challenged by an upstart young talent to a competition. And he’s worried that being old he might lose. And so desirous is he of winning, and so worried about being possibly shamed, that he runs off to the forest to escape the dilemma. But once in the forest he gets scared and starts thinking he might get devoured by wild beasts. So back he goes to the city. Where he gets worried again and heads once more for the forest – and he does this back and forth little dance for six days until Shakra, king of the gods, has had enough of it and tells him to have some faith in himself, and reassures him that he’ll win! And remember this worried guy is the Buddha in a past life!!

We all get caught. We all fall down. No one can stay on the mountain forever. And, really why should they? That is, why should we? After all, to conquer desire don’t we have to be where desire can arise?

So, to return to our jataka, it’s down on the ground, in the midst of temptations, difficulties, and possible failure that we find out what we’re made. And we can finally learn how to walk, not simply fly.

Then again – what do you think? Maybe it was a mistake for the bodhisattva to be drawn back down into the hustle of the city. Maybe his descent was proof of some shortcoming or flaw. Maybe he was restless, his mind wandering, (samsara means “wandering”) and so, maybe he goofed by leaving his safe mountain retreat. Did he really need salt and vinegar all that much?

But don’t we all sometimes do dumb things? If so, what then? Should we just ignore it and go on? NO! says this jataka. We can’t just go back to business as usual and act as if nothing happened. We need to let our errors transform us, by taking them to heart. Then when we say we won’t do that again, we will mean it. “Endless blind passions I vow to uproot;” “Greed hatred and ignorance rise endlessly, I vow to abandon them.” These are two translations of the second of the Four Vows, or Great Vows for All, the bodhisattva vows recited by all Zen students. They mean we’ll be serious, that we’ll really work at it, and that we mean business.

But when the Buddha went down the mountain, he didn’t just gather salt and vinegar, and then head home. No. He stayed for sixteen years, offering teaching in exchange for lodging and food. Was that a mistake? For, suddenly, one day, as if out of the clear blue empty sky—Wham! Thunder! Lightning! A firestorm! Flaming desire!! Does he then think: “Oh, man. I should have never come down from the safety of my mountaintop and gotten so comfortable! This is what comes from mixing about with ordinary, worldly people! I’m going back up onto my mountain, and I’m going to stay there forever!”?

No, he doesn’t. He doesn’t blame others. Lama Govinda, the early noted Western Buddhist, in his final book, which he saw as the summation of his work, A Living Buddhism for the West, writes:

When the Buddha proclaimed his teaching of the cessation of suffering, he did not speak of ‘avoiding suffering.” If this had been his aim, he could, according to Buddhist tradition, have chosen the short path to liberation, which lay within the realm of possibility for him at the time of the buddha Dipankara: he would have spared himself the suffering of innumerable rebirths. But he knew that only the one who has passed through the purifying fire of suffering can gain the highest enlightenment in order to serve the world. His path was not to flee from suffering but to overcome suffering to conquer it. That is why he, like the buddhas before him, was called a jina, a ‘victorious one.’ (Govinda. A Living Buddhism For The West, p. 83.)

And how do you conquer suffering? There’s only one way. You try, you fail, then you get back up, and try again, and again, and keep at it, over and over. Until the job is done.

So maybe the Bodhisattva got it right. Maybe he sensed that it was time for him to find out where he stood, time to see if he could be of some use in the world, time to see if all that meditation had done any good besides bringing him a measure of personal peace and the ability to fly, time to get back in the mix of other people, diverse views, desires, and problems, get knocked off his calm and lofty perch, then get back up and go on again.

(There is a tale in the Nepalese jataka tradition, the “Subhasa Jataka,” which does not appear in either the large Pali Jataka collection, or the smaller Sanskrit, Jatakamala, Rosary of Jatakas. In this little-known jataka the Future Buddha-to-Be’s whole bodhisattva career of four inconceivable eons and 100,000 kalpas of unceasing practice exertion which is said to span, four times 3×10 51 x 320×10 6 or four times nine hundred sixty thousand million million billion billion billion billion years, begins not with success, but with failure.

He’s a king back then in a previous world age, many universes back, long before our present universe took form. And he wants to go ride on his elephant. But the elephant then in rut, has broken its chains and charged back to the jungle. His elephant trainer comes before the king who’s waiting for his ride, and breaks the bad news. “Sire, your elephant has, uh, temporarily run off. Not to worry. He’ll be back in a couple of days as he is well-trained.” And the king just totally freaks. “What! I don’t get what I want, when I want it?! What kind of stupidity is this!?” And he throws a kingly tantrum like a total child and is shouting, and maybe even strikes the trainer, and tells him to get out of there and not come back till he has the elephant under his control again. “I mean, the idea. To come into my throne room and try to make excuses for such incompetence!” A few days later the trainer returns and says, “The elephant is back, Sire. You can ride whenever you want, your Majesty. Like I told you, he’s well-trained.”

And all at once the king is overcome by shame. The problem wasn’t controlling the elephant. It was controlling himself. He is a king and he doesn’t even know how to control himself, even as he’s controlling everybody else. Or trying to. It stuns him. He realizes that skillfully controlling, not repressing the self, that fluid, protean, unfindable, mysterious self, the me-ness of Me, is a tougher challenge even than trying to control a great elephant in its time of rut. Shades of the ox-herding pictures, billions of universes ago! And as a king, he decides that he must, he has to, that it’s incumbent upon him to take up that challenge.

So this line of the tradition begins the bodhisattva’s career here, with a recognition of a mistake and of failure, much further back than his more glorious and very positive meeting with the great Dipankara Buddha, Buddha of the previous world age, when he is already a sage, and already well on his way to Enlightenment. Instead, it’s failure that gets him going on his endless road. Failure, it turns out, has its uses, even benefits. We all wish it were simpler. But it wasn’t easy, even for the Buddha. So why do we think it should be easier for us?)

After recognizing how vulnerable to error he still is, the Bodhisattva feels shame, and he apologizes. Let’s give him his due. We have to like him. When first asked what his problem was, he truthfully says, “It’s lust.” He’s not a coward, or a hypocrite. He’s not making excuses, not saying, “Hey, I’m enlightened! I’m free! So whatever I feel like doing is ok, because when you’ve experienced the kind of profound emptiness and total freedom that I have, anything goes.” Or “You’re just not enlightened enough to understand.” Or, “Freedom is license.” Or, “I live in the Absolute.” Not at all. He’s struggling with it, examining himself by the light of sila. Roshi Kapleau, used to say, “When stuck, say you’re stuck. When you don’t know, say you don’t know.” In other words, don’t act like a Buddha when you’re not. Don’t be a wise guy or a show-off. So we have to like the bodhisattva-ascetic for being direct and honest. When asked what the problem is, he says right off, no dithering, “It’s lust.” The king likes him, too. He doesn’t think, “So, this guy is a sham, after all. I’m going to chuck him.” He can see that his teacher is hurting and, at the same time, he can see his potential for really mature wisdom.

The ascetic, once he sees what’s happened to himself, decides to head back up into the Himalayas to his old refuge. He doesn’t start blaming the king and queen and their worldliness, or the bad “vibes” of city living for his error. He accepts his error, appreciates their help, and sees, too, that he needs to go. But is this a kind of running away, a negative sort of beating a “retreat,” the very opposite of being a conqueror? Couldn’t it be interpreted as such? Maybe. But his intent seems to be to work hard on himself in order to clarify and deepen his practice and understanding so he can do better, not fall into the same error again, and one day be of genuine use to suffering beings. He’s not deciding to stay isolated forever. So we should expect to see him back in the world, back down the mountain, fully engaged with life, ready to offer deepened practice to the world, a practice built more solidly than ever on dana, sila, and all the other paramitas or perfections. Which is exactly what we do see in other jatakas.

The point of the jataka is actually simple—we learn and grow through difficulties. The Buddha’s own path began when as the prince Siddhartha, he was broken, torn wide open by the terrors of birth, old age, sickness, and death. It’s like he went out one day for a nice ride and suddenly saw a starving tigress. And had to take a leap. Struck to the heart, he didn’t leave his lovely family home to become an ascetic because it was “cool.” He did it because he had to.

Roshi Kapleau used to repeat a Japanese folk saying that went, “Seven times down, eight times up. Such is life.” Whenever he said it, I used to think, “Yeah. That is how we stumble along. Very true.” But I see now I missed the point. It’s not simply the sad but true way of things. It’s not even a presentation of a rather hopeful truth. Instead, it’s the very essence of the Path itself.

And how did it work out back then, twenty-five hundred years ago when the Buddha told this jataka about his own failure to a wavering monk? Encouraged by the Buddha’s example, the monk was able to free his mind and attain liberation. Without failure, there would have been no occasion for teaching, and so, no chance for liberation. It all hangs together. The failure was perfect, even helpful. Wonderful indeed! – to grab a little phrase from Mumon. (Mumonkan, case #42, “A Woman Comes out of Meditation.”)

And, who were the characters in this past life tale? The Buddha says that Ananda, his loyal cousin and attendant, he of “remarkable memory,” from whom, supposedly, all the sutras have come down to us, was the good king. The nun Uppalavanna, well-known for her wisdom and sensitivity, was the wise Queen, Gentle Heart. And he, the Buddha himself, was the honest ascetic-bodhisattva who had such a difficult, yet eye-opening and, ultimately, transformative time of it, way back when he was still unskillful and immature in his practice, many long ages ago.