Fairy Tales and Zen Riddles (from Tricycle Magazine, Winter 2005)

By Rafe Martin©

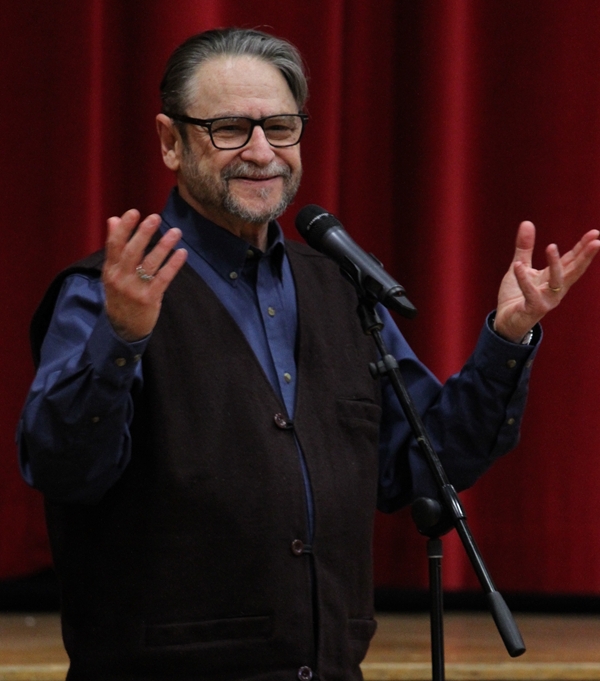

Rafe Martin was born into the perfect training ground for a storyteller. He grew up immersed in told stories, hearing his father’s tales of flying dangerous rescue missions in the Himalayas during World War II, fairy tales read aloud by his mother, and his Russian-Jewish relatives telling entrancing, often hilarious, stories about their lives. His early exposure to stories about Asia, his reading of Alan Watts and other Buddhist authors, and a chance meeting with Allen Ginsberg in a bar in Greenwich Village fueled his interest in Zen practice. In the late ’60’s, Martin found himself becoming disillusioned with graduate school at a time when the Vietnam War and social unrest were peaking. “I made a vow to myself in graduate school that if things got really bad, I’d go practice Zen,” he said.

Things did get really bad, and he began sitting with Philip Kapleau Roshi [1912—2004], the founder of the Rochester Zen Center, in upstate New York, becoming a student and, later, a disciple. It was at the Zen Center that Martin began telling stories, most of them Buddhist Jataka tales (stories of the Buddha’s former incarnations), and began learning firsthand the power of told stories and the role of a storyteller. It was also at the Zen center that he began melding his storytelling and writing with his Zen practice, which has included working with koans. Koans—sometimes called spiritual puzzles—pose questions or situations we can’t answer or understand using logic, and thus force us to go beyond the discursive mind. Martin recognized that the traditional tales he was using in his storytelling and writing might in fact function like koans. These simple tales may indeed point to our place in the universe.

Martin is the author of twenty-one books, ranging from picture books to novels, and he was the editor of Roshi Kapleau’s final two books. He has won numerous awards both as a storyteller and as an author, including the Storytelling World Award, American Library Association Notable Book Awards, and Parent’s Choice Gold Awards. His most recent novel is Birdwing (excerpt on final page).

I spoke with Rafe Martin this summer at his home in Rochester, New York.

—Joseph Sorrentino

Which came first, storytelling or Zen practice?

It’s very hard to distinguish, in a way, because I’ve always been interested in story, if not an actual storyteller. But by the time I came to Rochester Zen Center, I was interested in just sitting, in practice, just in getting my life together.

You once said, “I don’t think I could be a storyteller without Zen.”

I needed Zen practice because my mind was really not peaceful enough, not empty enough, not sensitive enough except to its own pain. And without sitting and experiencing the intimacy of everything around me, there’d be no foundation, no way for the words to emerge that would have real power.

How did sitting affect your storytelling?

I worked on stories as koans, and my job was to demonstrate the life of it, not to think or analyze. There are interesting experiences you get to when you tell stories. It’s not like you’re there telling stories. It’s like you’re not there telling stories, and the stories kind of emerge. I think a lot of that comes from sitting, of just not getting in the way of the story and not trying to promote yourself or protect yourself in the telling—you kind of drop away. For me, storytelling is like koan practice in front of a large group of people.

Is it as terrifying as dokusan [private instruction with a Zen teacher during which a student may demonstrate understanding of a koan]?

No, because there’s nobody there to tell you that you screwed up.

Does the audience experience this dropping away as well?

If I shout in telling a story, you stop thinking about the bills you have to pay, what’s going on in your life—your heart rate accelerates, your adrenaline releases. It’s suddenly not pretend, it’s real. That’s part of what happens in telling stories. It’s not discursive language. I could sit here and tell you about stories. You’ll think it’s smart, intelligent, thoughtful, but something different will happen when someone starts telling you a story: You’ll sink into it like it’s an ocean. And you’ll let go of stuff.

Why do we need stories? Why not something that says, “This is exactly what happened?”

Because we’d be lying. We don’t know what really happened. And even though they’re fictions, stories give us a doorway to truth, which is a great thing. Fiction is an untruth, but it’s a lot truer than anything else we can say because it tells us about what’s constant in the human experience—fear, suffering, courage, compassion. We also seem to have a psychological propensity for stories that carry deep emotion and deep meaning, and these are somehow more fundamental to us than our explanations and philosophies.

You once said that you were interested in the myth of Siddhartha Gautama’s life. Why “myth”?

The myth interests me because I realize it is the story of all of us—we’re sheltered as children, and then we discover the world can be a very hard place, a very painful, dark place with sickness, death, grief —and it freaks us out, and we see that maybe there’s a path through the darkness. There’s a path that involves leaving everything you know, everything you’ve been clinging to, everything you thought you were, and letting go of it. What the Buddha found was so deep, so all-encompassing, and it’s already there for everyone. To me, the myth is truth. We have two concepts of myth in our culture: Myth means lie, “it’s just a myth,” which I think is the lesser perception. Myth also means the highest level words can go before they merge into silence and say nothing. Joseph Campbell said that myths are clues to our spiritual potentialities.

It’s like these stories exist somewhere—call it Mind, I guess—but humans give it voice.

Yes, yes, humans give it voice—but we’ve lost our voice. We’ve forgotten what our voice is. Traditional stories are ways of checking in, like koans—they’re ways of checking in to see if you’re headed in the right direction or if you’re way off the path. How much of human life is way off the path? So are these just stories, kiddy stories, which should be relegated to the playroom? No. They’re life-saving. They’ve been around for countless generations because they do something for our minds and our psyches and our hearts that nothing else does, which is help us check in.

My understanding of koan practice is that it helps us to come to realization. Isn’t that what you mean by “checking in”?

Koan practice gives you a sense of what traditional cultures, that is, indigenous cultures worldwide, were experiencing in their own ways, and certain kinds of stories can be seen as expressions of those checking-in moments. We have to have, in a way, a fairy-tale aspect to ourselves. For example, as you say, dokusan can be scary, terrifying, which is stupid because all we’re doing is facing ourselves. We need courage—we have to go through thorns, we sometimes have to pick up our swords like Manjushri [the Bodhisattva of Wisdom] and cut everything—our delusions—down. This is the world we find in traditional tales, or what may be called fairy tales. They mark a trail that has a spiritual dimension that we re-find in Zen or other practices.

Koans are used in some sects of Zen Buddhism to help people get beyond the discursive mind. Some of these are taken from traditional tales. Did the Zen masters who developed koans recognize the power of traditional tales and tap into them?

They knew the sutras, out of India. They knew Chinese folk tales. That’s what they grew up with. I would say that the kind of spiritual geniuses that made use of or invented koan study were probably taking things from their past experience. They could dip into those experiences and see them from a nondual, unconditioned perspective, from the perspective of timelessness, of eternity, or whatever you want to call it. They were seeing from the foundation of mind itself, so everything—the fall of a leaf, the song of a bird, a folk tale—could express the deepest wisdom. I think they simply were able to take a folk tale and use it to point out where you’re at right now but you just don’t see it because your mind is full of all kinds of stuff. They used what was at hand. If there was a folk tale at hand and a teaching in it, they used it.

What’s so interesting about Zen is that the masters were so free to be able to take a little tiny piece out of a story and work on that: Here it is, here’s the whole thing in a nutshell. That’s really powerful. They were boiling down the whole tradition, this vast, voluminous sutra literature, into these tiny points—koans.

You’ve said, “Traditional tales are the koans of everyday life.” What do you mean?

Everyday life is about community and solitariness, about male and female, work and play. Yeah, I think traditional tales are the koans of everyday life.

To me, it’s seeing the miraculous in the mundane.

What is the world? It’s people living, breathing, making love, dying, birthing, cutting your hair. It’s also a lot of other stuff that isn’t so hot.

Roshi Kapleau used to say, “The mind illumines the ancient teachings and the ancient teachings illumine the mind.” That’s why I became a storyteller. That’s the relationship of Zen and stories. To me, that’s the nub of everything we’ve been trying to talk about. That’s it. That’s the whole thing, that our minds are transformed by coming into contact with deep narrative, and deep narrative is brought alive by our mind. You can have the scientific data explaining the world but it’s apparently not enough. We seem to need stories to come to a deeper understanding. Myth is the highest level of story. It’s story in which the nature of one’s identity is revealed or may get revealed. It’s the story in which we’re all embedded, which is the story of identity. Isn’t that the highest story? Myth to me is a story that touches on the nature of identity: who we are, where do we come from—that’s myth.

It’s like when you read a history of the Buddha’s life, you learn about him. But when you hear the myth told, you become the Buddha, you create that story for yourself. That’s why we need myth.

Yes. We become the Buddha of that story. For Christians, I assume, the Christ story is the story of their own life. The stories illumine fundamental aspects of ourselves, aspects that our present culture may not be able to awaken.

And without the story?

Without that story, you’re Joe Schmo with your particular family history and job and bills to pay and your death looming closer to you every day. But with the life of the Buddha, you are the Honored One who has already seen that everyone is already fully enlightened. So if you can illumine your life with that story, your life is transformed. That’s the power of myth. And that’s why I became a storyteller: When I entered the Buddhist tradition, I realized that I was back in a traditional world.

Once Upon a Time

The following is an excerpt from Birdwing, Rafe Martin’s new novel about a boy, Ardwin, who returns to his human form from his cursed swan body but still has one wing and a taste for the open sky. Here Ardwin speaks with his brother about what it was like when they were swans:

After supper, they sat together, chairs drawn up before the fire. Ardwin looked into the flames and asked, “Do you ever think back to the

Time?”

“The Time’?” repeated Bran. “Just what ‘time’ do you mean, little brother?”

“Why do you do that?” asked Ardwin, annoyed. “You know, when we were swans.”

“Ah,” Bran answered, looking at Ardwin. “Of course I think back to it. As if I could forget. And when I do, it still makes me furious! That witch’s spell creeping over us like numbness, like drowning. First my toes disappeared, then my legs and arms, gone.” He shuddered. “Then up it crept, taking my neck, my human tongue, my face. And there I was, neither bird nor boy, my mind flapping about like a creature caught in a snare, no longer itself, nor yet something else. Ugh. I’d be happy to forget forever—I wish I could. Thank goodness it gets more distant each day.” He lifted his mug. “Cheers!” He took a long swallow.

Ardwin said, “It terrified me too at first. But there were things about it I� Don’t you miss the flying?”

A log crumpled softly into the coals with a quiet hiss.

“No. Are you crazy?” exclaimed Bran, running a hand through his thick brown hair. He shook his head. “I don’t miss it. I like it fine where I am, with both feet on the ground and Elsbeth by my side. I don’t miss the rain and wind, the cold and dark. I don’t miss those muddy shores and icy marshes and snow and hail. I don’t miss the stink of rotting reeds and swan turds. I don’t miss not being able to talk, or sing, or sit by a fire. I don’t miss not being able to hold a sword or a cup or a wife. Why should I? It was a curse.”

“Yes, of course. But don’t you miss…the wildness? Having wings? Feeling the ground drop away beneath your feet, and finding villages, castles, towns, forests, lakes, mountains, and seas spread below!” Ardwin closed his eyes, remembering. “Pine smell and ocean salt, marshland and forest. Smoke coiling up from a woodsman’s fire, lofts of cloud and precipices of stars, the dark earth tugging below, and us, together, flying in that windy wildness so free! Don’t you miss knowing what birds and animals say? Bran, I remember the flocks flying, thousands of swans filling the sky, our wings beating, our voices calling with the rest. I felt like I was inside some old saga, each of us a single word in the story. Don’t you miss that at all?”

Bran thought about it, and he shrugged. “No, not really. I had to do it and I had no choice. And now it’s done, thanks to Rose. Remember, I said to all of you, ‘Rose will save us. She said she would and she will.’ Every day I kept us together as a flo… as a group. Remember how I killed that fox that tried to grab you?” He looked at Ardwin, who nodded back. “I beat it with my win… my arms, and pecked it with driving blows of my bea.. my head, til it was dead. That was the best thing that happened the entire time, that and Rose saving us. She did it, brave girl. I’m proud of her and eternally grateful. But no, absolutely not. I don’t miss it at all.”

Ardwin’s face fell. “Not even when wild geese call and swans fly?” Bran sighed and looked into the fire. He tapped his hand on his knee, then turned to Ardwin. “No,” he said.